The only way to perfectly estimate how long a task will take, is to do the task and measure how long it took. In most situations where you’re endeavoring to produce an estimate, this is not a practical way of providing it. At the other end of the spectrum, you can pick a random number and base your timeline on that. While this is a quick and easy way of coming up with an estimate, it is rarely helpful. Between these two extremes is where most of us end up; balancing the tradeoffs between accuracy and impracticality. Story points, and the various ceremonies that surround them, are an attempt at striking that balance.

Software developers often use story points within some variation of agile framework to communicate their estimates to their project managers and fellow teammates. Despite their pervasiveness in the industry, story points have no consistent definition, and there is often ambiguity about what they represent. To make sure we’re all on the same page, I define them as:

A relative measure of the estimated amount of effort required to complete a task.

The word “relative” is doing a lot of work here. A senior developer may complete a task in half the time it takes a junior developer, but this shouldn’t change the estimation of effort. Because of this relativity, story points become most useful in aggregate. There, they are used to describe a team’s velocity - the number of story points a team can be expected to accomplish over a sprint (usually a two week period).

Another word doing a lot of work in that definition is “estimated.” As I mentioned at the start, an estimate will never be perfect and will always carry some level of “uncertainty.” Unfortunately for story points, they are a single number and have no built-in mechanism for conveying that uncertainty. A nod to this drawback is found in the commonly used practice of only assigning story points from values in the Fibonacci sequence. 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, etc. By omitting 4s and 6s, we acknowledge that our estimates are not precise enough to distinguish among the numbers surrounding five.

While acknowledging uncertainty is easy to agree to in theory, it is often forgotten in practice. High point values can become dumping grounds for significant (but well defined) work, and small values can describe the “best-case scenario” of a volatile undertaking. In my own estimating, I try to stick to the agreed-upon precision, and measure my story points as “effort + uncertainty” as follows:

- 1 point. I pretty much have the entire task written in my mind; I only need to type it out.

- 2 points. Similar, but the amount of work to be done exceeds my working memory. I can’t keep the whole thing in my head at once, so I may be missing something.

- 3 points. Some unknown element has been introduced. Documentation will need to be read, or multiple avenues will need to be explored.

- 5 points. A significant unknown element is involved. Either documentation doesn’t exist, or the task involves components (or people) that have a reputation for being difficult.

- 8 points. Uncertainty levels are such that I’m basically asking for a full sprint and not even promising to have a deliverable at the end. I will need to do some research, and I don’t even know where to start.

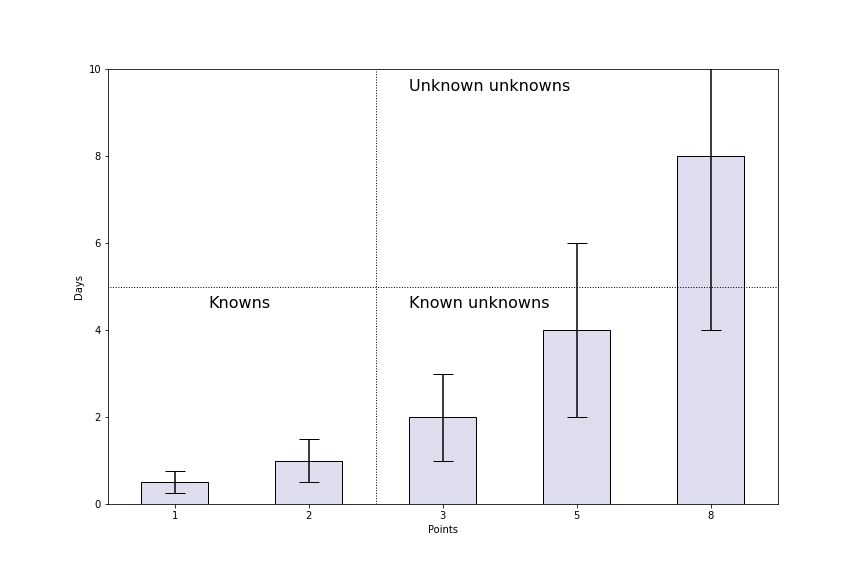

Plotting these point values against my typical velocity looks something like this:

Conveniently, this fits nicely into a four-quadrant graph.

- Knowns. There is a known amount of work involved, with very few surprises - generally, a continuation of existing work.

- Known unknowns. There is an unknown amount of work, but the kind of work is known. Usually, this involves adding new functionality, particularly with external integration points.

- Unknown unknowns. Not only is the effort required a mystery, but it’s hard to know where to start. These show up more frequently at the start of a new project and are the most likely to blow up a timeline.

- Some unnamed fourth quadrant with nothing in it.

I have found this to be a reliable framework for delivering estimates that are of consistent accuracy. It also provides a useful distinction in meaning between different story point values. A five is not merely a collection of ones. However, to take advantage of this framework requires that the tasks themselves have the appropriate balance of size and uncertainty.

5 != 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1

How should we handle a big task full of a bunch of clearly defined work? Break it up. In addition to the new collection of single point tasks aligning themselves more closely with their implied precision, this conveys several other benefits. Namely:

- It’s satisfying to finish what I’m working on at the end of the day and not have to pick it back up and figure out where I was the next day.

- No one wants to code review a week’s worth of work, especially with the line count of a week’s worth of simple work.

- It’s an opportunity to catch unknowns faster. If the first task takes two days instead of one, what happened? Will the rest take twice as long too?

Bimodal probability distribution

Sometimes I see a task that I know will take one day or one month, but almost definitely not one week. An example would be doing some analysis on a large dataset, right on the cusp of what a single machine can accomplish. If it fits in memory, it will be a straightforward process; I can use the tools with which I am most familiar and iterate rapidly. If it doesn’t, then I need to implement a distributed system. Results will come more slowly, and I’ll need to add managing the computation cluster to my todo list. The solution here is to create a new task - a timeboxed research task to determine which of the two paths I’ll be going down. Once I’ve eliminated one of the two “modes”, I can feel free to estimate the remaining work using more normal probability curves.

Some final thoughts

What I’ve just described is a tiny slice of what goes into putting together an estimate. I’ve explained my thought process as an individual estimating a single task. In reality, story point estimates are a dialogue with the rest of your team and take in the rest of the project as context. That dialogue is crucial to flush out hidden requirements and ensure that everyone agrees on the task’s entire scope. Finally, one of the most significant benefits of generating and tracking story points is revisiting them once the task is complete. Using past estimates to calibrate future ones is a form of deliberate practice that will inevitably improve your skill over time.